Behold the wise Jobst Rider,

Whose unfettered mind

Sees God in dirt

And hears him in the spokes.

(Adapted from a quote by Alexander Pope)

Jobst Brandt, a cyclist who in so many ways influenced the bicycle industry during its glory days of the 1980s, died on Tuesday, May 5, 2015, after a long illness. He was 80.

The day after his 76th birthday, Jobst crashed his bike at the Sand Hill Road and Whiskey Hill Road intersection near Woodside during an early morning ride in a dense fog. It was his last bike ride. His serious injuries added to the burden of other health liabilities.

Jobst exerted considerable influence over those he knew in the bike industry, but he was not an industry insider. Because he never worked in the bike business, he could offer his opinions about the industry without reservation.

His passing is a personal loss for me. I met Jobst in 1979 while working at Palo Alto Bicycles. I’ll never forget seeing Jobst wheel into the store on his huge bike, which he always rode into the shop while deftly opening the door.

He immediately bound upstairs to the Avocet headquarters where he would engage owner Bud Hoffacker in lively discussions (browbeat) about everything under the sun involving bike technology.

Jobst was like that. He believed with 100 percent certainty that his way was the right way. If you disagreed and didn’t have the facts to support your argument, you were just another crackpot.

Consummate engineer

Most of the time Jobst was right. He had that rare skill in a mechanical engineer — he not only understood engineering principles, he could translate theory into meaningful product improvements, whether it be a bicycle shoe, a floor pump or a cyclometer.

Jobst received seven patents (3 cycling), testimony to his abilities.

1 – 6,583,524 Micro-mover with balanced dynamics (Hewlett Packard)

2 – 6,134,508 Simplified system for displaying user-selected functions in a bicycle computer or similar device (for Avocet)

3 – 5,834,864 Magnetic micro-mover (Hewlett Packard, and Bob Walmsley, Victor Hesterman)

4 – 5,058,427 Accumulating altimeter with ascent/descent accumulation thresholds (for Avocet)

5 – 4,547,983 Bicycle shoe (for Avocet)

6 – 4,369,453 Plotter having a concave platen (Hewlett Packard)

7 – 3,317,186 Alignment and support hydraulic jack (SLAC)

He received his first U.S. patent while working at the two-mile long Stanford Linear Accelerator in 1966; he was recognized for his work on suspension for the particle accelerator. There’s a plaque with his name on it in one of the lobbies.

At Porsche he designed race-car suspensions, after quickly moving through the ranks. The way he got his job is classic Jobst. The young Stanford University graduate (his father was an economics professor at Stanford), who spent time in the U.S. Army in Germany as a reserve officer — lieutenant, then captain — in the 9th Engineer Battalion, approached Porsche and told them that their English translations lacked polish. Porsche agreed and he was hired.

Cycling legacy

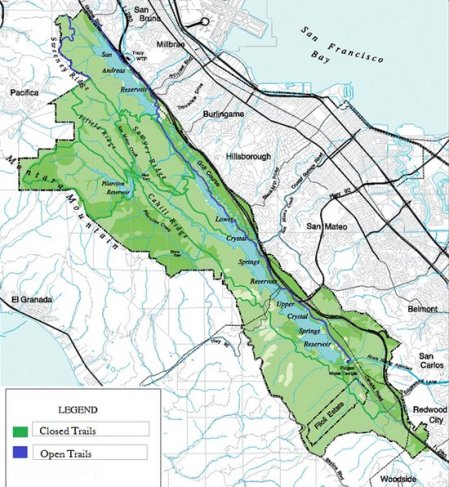

Jobst blazed trails beyond bike product development. His freewheeling way of thinking led him to do things most people would never dream of — like riding a racing bike with tubular tires on rugged trails in the Santa Cruz Mountains.

It’s not that big a deal, but other cyclists thought it was, so Jobst quickly gained a reputation that drew elite cyclists from the Bay Area to join him on his Sunday rides, starting promptly at 8 a.m. from his house on Middlefield Road in Palo Alto.

By the mid-1970s, Jobst had such a large following that some rides counted up to 20 riders. Most would not complete the ride, mainly because it lasted all day and went through creeks, over rocky trails lined with poison oak (Jobst was immune) and through private property.

While Jobst had an entourage of bike racers, he never had anything kind to say about the sport. I think the only good he saw in it was a test of a person’s mettle (a bike’s metal too) and the ability to overcome obstacles. That’s what Jobst was all about.

He never showed fear or got rattled in difficult situations. These Übermensch qualities came to the forefront when he fell and broke his leg at the hip in 1986 on the rain-slick pavement of Col de Tende. He got up, cursed himself for not recognizing the foam on the road, and ordered me to lift his leg over the top tube so he could coast to the next town.

In Tende, Jobst dismounted and crawled on hands and knees up the steps to the doctor’s office.

On another occasion he was trying to help a snake off Calaveras Road; it bit him and only then did he realize the young reptile was a rattlesnake. He didn’t panic, but rode back to his car in Milpitas and drove to Stanford Hospital for the antidote. The venom mangled his thumb.

One beautiful spring day in 1982 we were bound for Gazos Creek Road when we came upon a scene of absolute devastation. The road had been obliterated by torrential rains that downed redwoods and dislodged boulders the size of cars. Instead of turning around, Jobst urged us on.

So we clambered over trees and followed the creek downhill, eventually reaching a recognizable road after a mile of walking.

The Bicycle Wheel

Jobst wrote a lot (check out rec.bike or Sheldon Brown’s website), but nothing was more important to him than his book on the bicycle wheel. He spent more than a decade writing the book with the intention of producing a tome that would stand the test of time.

I learned to build my first set of wheels using his book when it was still in manuscript form. It was the first time I read a description so well done that I could follow along and build wheels that would last for many years.

Jobst let many people edit the manuscript, but it was Jim Westby, Jobst’s friend and manager of the Palo Alto Bicycles mail order catalog, who did the heavy lifting. Jobst also published a German edition.

The book has sold well since being published by Avocet and is still in print. It could be in print 100 years from now because the principles of wheel building are never going to change. Sure, thanks to new materials we now have 16-spoke wheels, but it’s a number that made Jobst cringe.

Love for the Alps

Although Jobst rode most of his miles in the U.S., he always made time for the Alps. For 50 years he rode there annually, riding many of the same passes year after year, with some variation. He almost always went with another rider.

Riding with Jobst in the Alps tested friendships. He became obsessive about riding all day, every day, and I don’t mean until 5 p.m. He liked to ride until 8 p.m. after starting around 8 a.m., when he could coax the hotel owner to get up that early.

If you rode in the Alps with Jobst, you knew you were going to cover a lot of ground and you could expect some adventure riding, sometimes sliding down snow-covered slopes when crossing high passes on hiking trails. Of course, Jobst rode all but the rockiest trails.

Jobst took many photos of his exploits over the decades, probably more than 10,000 slides. He had a unique ability to capture great photos with his Rollei 35. A few of his photos were made into posters and sold by Palo Alto Bicycles.

He could be obsessive about getting just the right shot, as when we were on the section of road supported by concrete beams looming over Bedretto Valley, Switzerland. Given the right cropping, the road appears to be suspended in mid-air, the village of Fontana 1,000 feet below. Possessed with taking the perfect photo, Jobst hacked away, limb for limb, at a sapling growing next to the road.

Wheel suckers

Although Jobst sometimes had a harsh demeanor, he had his fun side too. He loved to pull pranks and make puns while out on the road. We passed the day telling stories, jokes, and commenting on world affairs.

That was when we weren’t struggling to stay on Jobst’s wheel in his younger days. It was especially true with Tom Ritchey along for the ride. The accomplished racer and frame builder had a way about him that caused Jobst to push the pace; maybe Jobst did it to prove a point or just because he knew he could have some serious competition with Tom.

Whatever the reason, we had some hard and fast riding ahead of us on many a Sunday. It got even worse when other racers showed up, like Keith Vierra, Sterling McBride, Dave McLaughlin, Peter Johnson, Bill Robertson, the list is lengthy.

It got so competitive that we sprinted for city limits signs.

I could go on about Jobst, but it would require a book-length blog. I’ve published some accounts of past rides here (Once Upon a Ride) and they’ll have to do for now.

As Jobst was always fond of saying, “Ride bike!”

Excellent read: The Force Who Rides by Laurence Malone.

You must be logged in to post a comment.